The Paradox of Capitalism: Balancing Free Markets and Regulation

Exploring Adam Smith's Legacy, Economic Cycles, and the Role of Government in Sustaining Prosperity

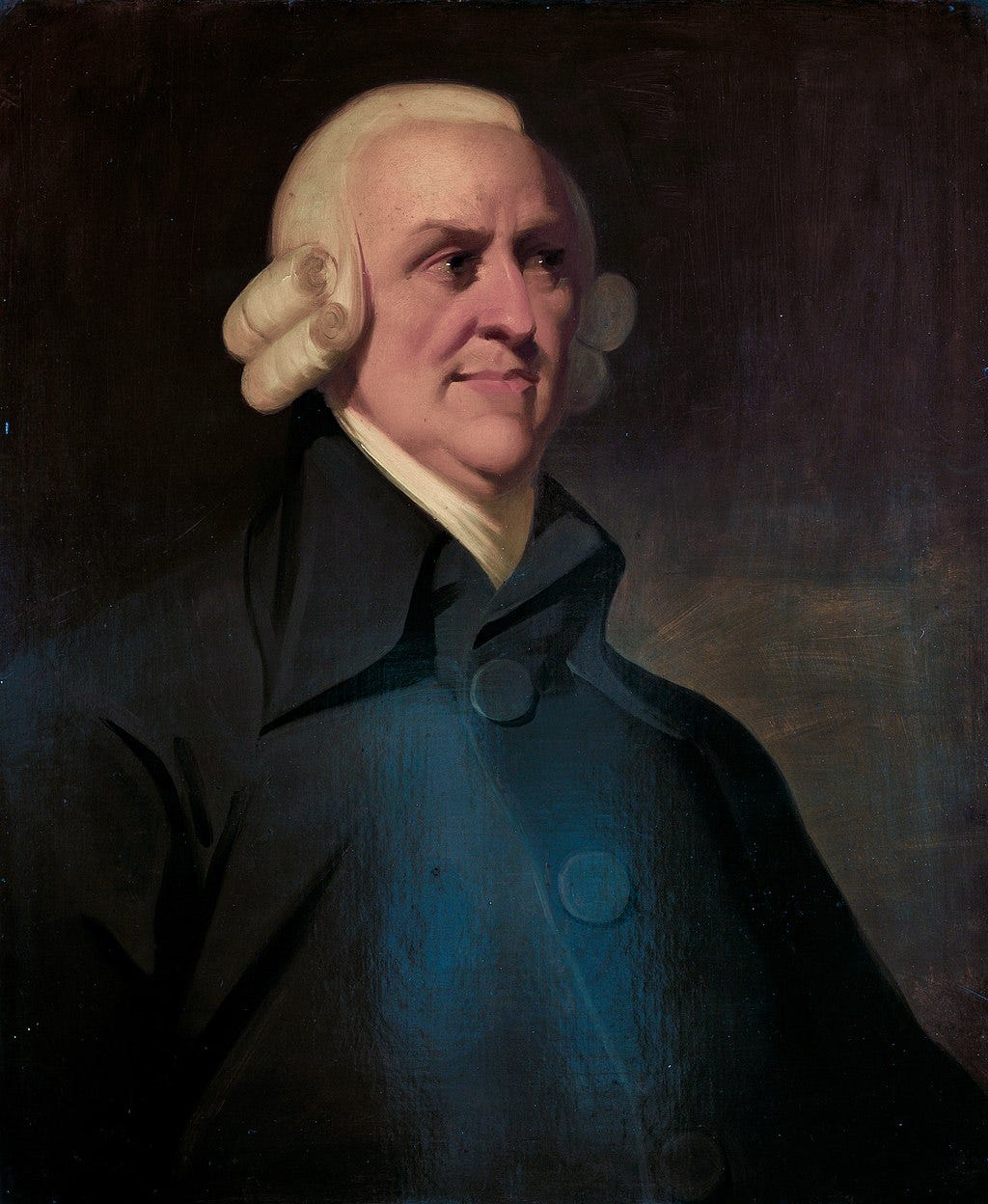

Adam Smith and Free-Market Capitalism

Adam Smith, a Scottish philosopher, widely regarded as the father of economics, was a fierce champion of free markets and the unparalleled benefits of capitalism. In his seminal work titled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, he famously stated that, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner but from their regard to their own self-interest.” An economy that operates via the exchange of goods and services among its population operates most efficiently when the forces of individual preferences and their corresponding access to resources can interact seamlessly. Over the course of the 19th to 21st century, it is evident that the countries which have successfully been able to make huge leaps in economic growth have done so by embracing the forces of free-market capitalism. Countries such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom were able to rapidly industrialise specifically due to the workings of free-market capitalism, pushing to secure lower costs of production through machines and capitalising on the abundant availability of cheap energy. Even the economic prosperity of a country such as communist-party run China can in large part be attributed to the forces of free trade and capitalism, as it positioned itself as the factory of the world and opened its economy to foreign trade and capital.

Figure 1: A portrait of Adam Smith by an unknown artist

The Cyclical Nature of Capitalist Economies

It would then seem Smith’s hypothesis that free-market capitalism is the ideal path for a nation to augment its wealth is accurate. However, a quick look at the various failings of different economies in the past suggests a hitch in the theory. It is undeniable that capitalism begets cyclical patterns of booms and busts. An economy may at one point begin to heat up, leading to expectations feeding into each other and causing the formation of a bubble (wherein asset prices and business ventures are characterised by exuberance). A certain negative event may trigger the bubble to burst, leading to negative expectations feeding into each other and causing a recession or even an economic meltdown where asset prices crash due to panic, businesses are shut, economic activity recedes, and the economy comes to a grinding halt. The cyclical nature of the economy, however, does not disprove Smith’s hypothesis. As shown in the figure below, there is still an overall positive trajectory where each low is higher than the previous one, and each high larger than the previous.

Figure 2: Business cycle and real economic growth in the long run

Some economic thinkers after the age of Smith have theorised that the government should step in with adjustments or interventions to smoothen the cyclical nature of the economy, trying to cool down an economy when it overheats and stimulate it when it performs poorly. The questions one must then ask are: How should regulators intervene? How far should a regulator go? And what objectives should the regulator pursue? There are no clear answers to any of these questions. However, the consensus is that regulators must prioritise sustainable economic growth, low inflation, and low unemployment. It is also the prerogative of regulators to address redistributive concerns by ensuring that their actions do not promote inequality and that they actively work towards a more equitable outcome. Therefore, a government that truly adheres to the principles set forth by Smith may reduce barriers to trade, allow free capital flow, protect property rights and the rule of law, provide certain public goods (such as roads, defence, education and healthcare), and, most importantly, avoid any form of policy that may lead to a repression of the free market.

The key component of capitalism is the channelling of the factors of production to profitable ventures while considering the various risks involved along with the possible payoffs. If an undertaking were to fail, it would be upon the promoter who undertook the risk to bear the costs related to it. If someone were to have insured the venture by subsuming the risk involved at a cost to the promoter (underwriting), then this individual (underwriter) would be liable for it. In periods of exuberance, individuals may undervalue the risks and overvalue the payoffs, leading to them undertaking risky ventures. When the cycle eventually turns downwards and causes many risky ventures to fail, many promoters and underwriters who are heavily leveraged are liable to pay. However, these individuals are unable to do so, and the economy finds itself in a state of free-fall where a feedback loop causes lower economic activity, lower incomes, lower spending, lower profits, unemployment, and so on and so forth. This is precisely the moment that a regulator (the government and/or the central bank) steps in to stimulate the economy and forestall the recession.

Figure 3: Chicago Federal Reserve Bank building

Case Study 1: The Savings and Loan Crisis (1986-95)

In the period between 1986 and 1995, the United States went through a deep economic and financial crisis involving fixed-rate mortgage lending, when more than 30% of the savings and loan associations (thrifts) failed. The Savings and Loan Crisis began with regulatory changes allowing thrifts to engage in riskier businesses, such as lending to commercial real estate and making high-risk loans, driven by exuberance and the chasing of profits. Thrifts aggressively expanded, leveraging heavily and investing in speculative ventures, particularly in the American southwest. When property prices collapsed in 1986 due to interest rates being raised to clamp down on inflation, many borrowers defaulted on their loans, creating a cascade of failures. Insolvent thrifts could not cover liabilities, leading to mass foreclosures and a deepening economic contraction. The government created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) to liquidate or sell off insolvent thrifts. To fund this, Congress authorised $105 billion, raised by issuing bonds through a government entity backed by taxpayers. Taxpayers absorbed the costs since the FSLIC’s (Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation’s) reserves were depleted and thrift failures surged, leaving the RTC to sell assets often below their book value to stabilise the economy. Losses were transferred to the public, costing $124 billion by 1999, despite the common citizen’s lack of direct involvement in the thrift failures.

Figure 4: Ronald Reagan, the U.S. president in office during the start of the S&L crisis

Case Study 2: The Great Financial Crisis (2007-08)

Another more recent failure to examine is The Great Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 that stemmed from a housing bubble inflated by subprime lending and securitisation. Financial institutions offered risky, adjustable-rate mortgages indiscriminately including to less creditworthy borrowers, driven by high demand for mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Banks packaged these loans into derivatives, earning high profits while underestimating risks. As home prices peaked in 2006 and interest rates rose, defaults surged, collapsing the housing market. The contagion spread globally, freezing credit markets as MBS values plummeted. Major institutions, such as Lehman Brothers, failed, while others required government bailouts. The U.S. government responded with $700 billion in funds under a newy created Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), quantitative easing, and federal guarantees, transferring losses in the process to the public, or socialising the losses. Unemployment doubled, millions lost homes, and the GDP contracted sharply, leading to the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

It is clear here that the forces of free-market capitalism were perverted by the regulators, whose actions in their capacity as fiduciary trustees of public interest not only restructured the incentive system by transferring the costs of risk to those who were wholly outside the undertaking (the common citizens) but also by promoting inequitable outcomes. Notable investors Warren Buffet and the late Charlie Munger have famously stated that, “Any institution that requires society to come bail it out for society’s sake should have a system in place that leaves its CEO…and his spouse, dead broke.” Moreover, by providing a blank cheque to all ventures that unsustainably pile on risk, the regulator worsens the cyclical motions of the economy rather than fulfilling the original objective of smoothening it.

Figure 5: Berkshire Hathaway Annual General Meeting Afternoon Session (2011)

Preserving the Core Principles of Capitalism

Economists Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales observed that, in the context of the most recent U.S. bailout of the uninsured depositors of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), many firms that keep deposits in banks do not practice basic risk management. They further noted that there were multiple other solutions that imputed the costs involved of the failure to the depositors rather than the common citizen, such as a 10% haircut on deposits or an insurance fee to be paid. They argue that a better policy for firms going under would be to provide a safety net for the people to ensure that the firm is allowed to “go bust” but the people do not. They assert that the failure of inefficient firms is an essential process of the creative destruction involved in Smithian free-market capitalism.

Smith had poignantly stated many centuries ago that, “Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor.” It is imperative that governments do not succumb to the political and monetary pressures of corporations. The great wealth of a nation cannot be secured when the forces that augment it, namely that of the free market and fair incentive and risk-reward structures, are subdued in favour of protecting undertakings that wish to operate without any regard to risk or liability. There are ways to intervene to protect the fundamental streams contributing to the prosperity of a nation’s economy while maintaining an equitable society that is subject to justice, the rule of law, and property rights.

Disclaimer

This Substack does not provide investment advice.

The author is not a SEBI-registered investment advisor.

The content in this article is intended solely for informational and discussion purposes. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instruments or other products.

Investors should seek personalized advice from their tax, financial, legal, and other advisers regarding the risks and benefits of any transaction before making investment decisions.

The information provided in this article is sourced from generally available information It may be incomplete or summarized.

Investing in financial instruments or other products involves significant risk, including the potential total loss of the invested principal. This article and its author do not claim to identify all the risks or key factors associated with any transaction. The author of this website is not liable for any loss (whether direct, indirect, or consequential) that may result from the use of the information contained in or derived from this website.

Government is inherently regulatory. That's how they make rules that we must follow and they don't have to, so they can get ahead and keep us controlled.

Regulation comes from authority, and all authority is illegitimate. Think of the first time anyone ever took authority over someone else. What did that involve? It involved violence or the threat of violence. Because if people actually wanted to do something, you wouldn't have to make a rule. They would just already be doing it.

The rule of law is our enslavement. The "law" of the jungle is our freedom.

Of course, those who rule by law will tell the opposite and claim that the law of the jungle is so terrible and awful and brutal. But what do you call the world we live in now? Is all of those things to boot.

To be free means having no government and therefore no regulation. Consequences occur naturally, both good and bad. We don't need fabricated ones meted out by courts. The court process is what perpetrators invented so slow down the justice that would have otherwise swiftly befallen them.

Please write more about economics - Anand sir and Shashwat anna